Decision Quality

(This article first appeared in Founding Fuel)

I love this graphic created by Tim Urban (@waitbutwhy). The possibilities from the present to the future are numerous. However, we can walk on only one of the many possible paths. The random path that we end up on becomes our life-story, while all other possibilities get automatically discarded.

We think a lot about those black lines, forgetting that it’s all still in our hands. pic.twitter.com/RSZ1d3W642

— Tim Urban (@waitbutwhy) March 5, 2021

When making a decision, we are blind to the future, which is yet to emerge. In the absence of a crystal ball, how can we make better decisions today? Should we simply learn from our positive outcomes and make more of such decisions? And shun decisions where the outcomes have been negative? Or, is there an intrinsic quality to decision making, that does not need any knowledge of the outcome.

The quality of a decision

Can a decision intrinsically be good or bad? Indeed. There is an entire branch of Decision Analysis called Decision Quality!

Decision quality (DQ) is the quality of a decision at the moment the decision is made, regardless of its outcome.

In most situations, we know what is the right thing to do. That we are not able to do the right thing is a different matter altogether.

A hundred years back, the great economist and investor Lord Keynes proclaimed,

...we are more concerned with the remote future results of our actions than with their own quality or their immediate effects on our own environment.

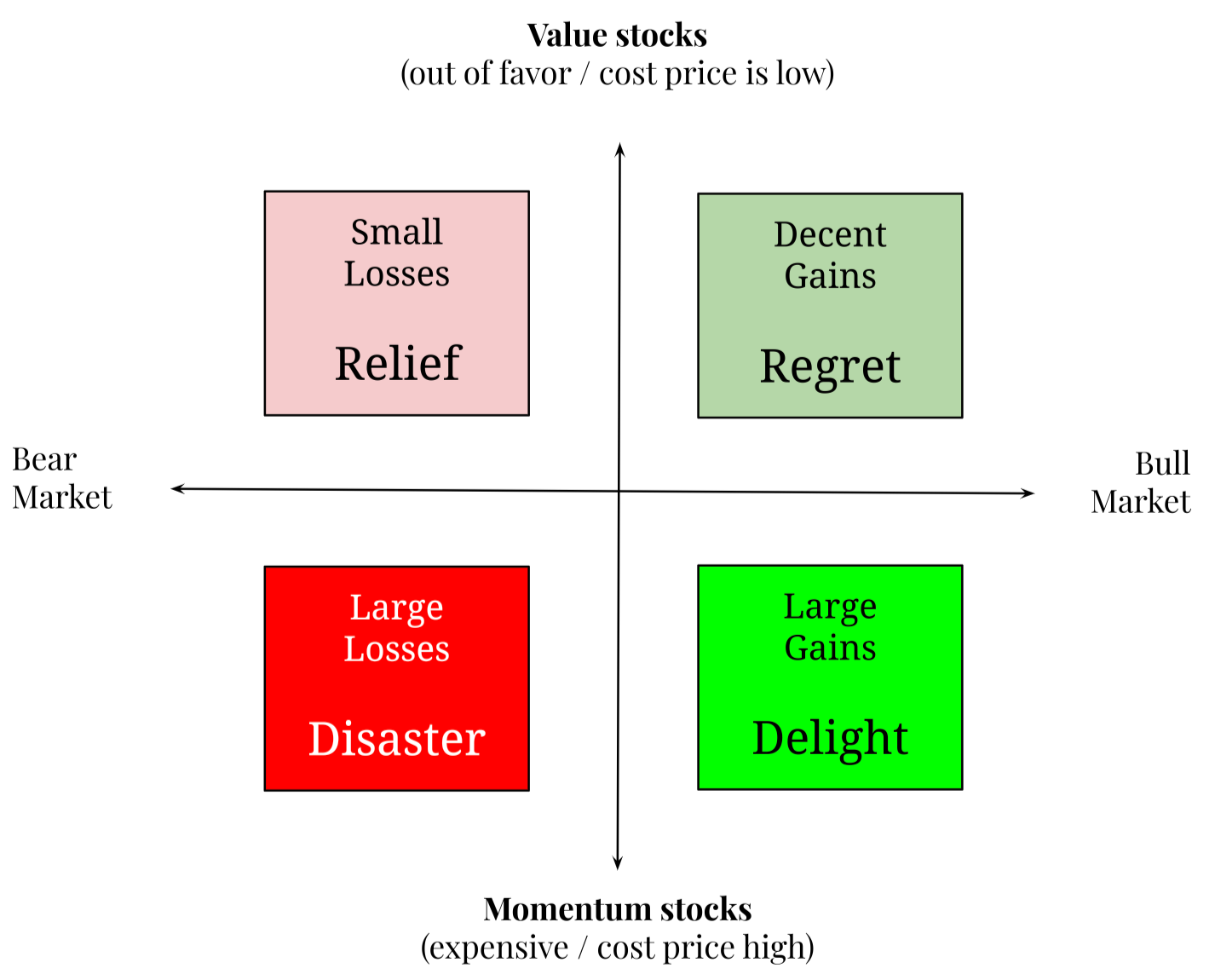

Consider investing. Most investors prefer to chase momentum stocks that have gone up 2x-3x recently. The daily increase in the price of a stock is proof that it can go up much more in the future. When the going is good, these investors make the most money. But when the music stops, which it always eventually does, these stocks also correct the most, leading to substantial losses for such investors.

The above matrix shows that the momentum style of investing is full of drama. In comparison, value investing is utterly boring.

Chasing the latest, over-expensive thing has to be recognized as a low quality decision, even though the investor may actually make money some of the time. (This does not imply that investors who buy cheap, beaten-down companies will always make money. But, on average, their survival and success rate will be higher than the momentum investors.)

Improving decision quality is about increasing our chances of good outcomes, not guaranteeing them.

Even when that effort makes a small difference....it can have a significant impact on how our lives turn out.

Examples of Decision Quality

| Situation | Decision Quality | |

| Good | Bad | |

| Equity investing | Invest in a good quality company with high ROE/ROCE; management is credible | Invest in a stock whose price is going up, regardless of the business or management |

| Using Leverage | Never invests using other people's money | Leverages securities, house to invest in stocks |

| Investing in startups | Invest in the founder. Idea secondary. | Investing in a startup where the idea and numbers are good, but the founder appears shady (cocky, disingenuous) |

| Golf: your first shot is in the trees | Come safely out of the trees before anything else i.e. chip out | Find a narrow space between the dozens of trees and try to hit the green. Watch this video for laughs! |

Decision quality ≠ Outcome

The biggest problem in decision making is that we typically equate the quality of a decision with its outcome. Annie Duke even invented a word for this: "Resulting"; reflecting on the decision in light of the results.

Imagine a fund manager who has invested in an out of favor sector. Till the sector does not turn around, the market views this manager as inept.

The board of a company appoints a new CEO. After a year if the CEO does not work out, the decision is now retrospectively considered as a bad decision.

In a bull market there will be new upstart funds that will make stratospheric returns. (Quant funds being the current flavor in India). Investors are rightly skeptical of these players in the beginning, but after watching month after month of high returns, they are forced to throw in the towel and invest in these funds. Who can argue with the data, right?

However, this kind of naive, outcome-based thinking makes absolutely no sense in areas like investing which are complex and uncertain.

Outcomes don’t tell us what’s our fault and what isn’t, what we should take credit for and what we shouldn’t. This makes learning from outcomes a pretty haphazard process.

Lucky outcomes can do more harm. Sometimes, a fundamentally bad-quality decision can end up generating a great outcome. When this happens, instead of considering ourselves plain lucky, we think it is okay to make bad quality decisions. In essence, such twisted experiences compromise and corrupt our decision-making process.

Most active equity investors hold some percentage of cash in most parts of the market up-cycle. They are perfectly aware of short-term opportunities where the cash can be deployed and quick money made. Still, they continue to ignore the opportunity costs that come from holding cash. What explains this?

It is not that they dislike generating returns. But what they dread is that if they start on this short-term investing path, it will screw up their long-term process. The tactical cash is the dry powder that will be used in the next bout of volatility when the market presents no-brainer opportunities; and not to trade in mediocre 10%-20% opportunities.

The hardest thing to do is to sit with cash. It is very boring.

Here’s another example: Consider an investor who has been investing for a few years. Influenced by his friends and broker, he takes a loan by pledging his existing securities or property, thereby leveraging his investing corpus. As the returns start coming on this large base, he wonders why he did not try this great idea before.

Enter the next bout of market volatility, which has a habit of coming around like clockwork. When the music stops our investor finds himself without a chair. The stock holdings crash and the margin calls come. Since he has no cash, he is unable to pay the margin money and the bank ends up selling all of the securities. Our investor has lost all his investments.

Borrowing money to invest is a fundamentally bad-quality decision, even if it makes large money. No wonder the patron saint of investors has this to say,

Three things ruin people: drugs, liquor, and leverage.

Good quality decisions can lead to bad outcomes. A bad outcome does not always mean that the decision was bad. Many times, good quality decisions can lead to bad outcomes.

In 2018, I happened to invest with a celebrated fund manager who had left a large fund to set up his own. It was his conviction that private banks, NBFCs and consumption were over-valued. Instead, he loaded up on contrarian bets in industrials, pharma and IT, with the belief that the industrial cycle would turn.

A couple years passed but his thesis did not pan out. The fund was down 40%. However, just after covid, things started unfolding exactly as he had envisaged and the fund doubled (from the lows) in a very short time.

In the 5 years that I have remained invested, the fund's returns are around 65% – not bad, but nothing notable compared to his peers.

How must we process this outcome? If I could go back to 2018, should I invest again with this manager? Absolutely, I must. On the many paths that emerge into the future, this manager will generally come out tops on more paths, but not on all paths. He just happened to get “unlucky” in this case.

Philosophers say that the end does not justify the means. What they possibly imply is that there must be an intrinsic morality attached to the means. Hinduism calls this dharma, or doing the right thing per se.

Likewise, when making decisions, especially the long-term and important ones, we must strive to make fundamentally good-quality decisions, irrespective of the outcome. This does not mean that the outcome will be positive all the time, but it will be hopefully more of the time.

A probabilistic future outcome cannot always justify a decision that we make today. Life is too short for that.

Related post

Member discussion