Embracing Market Fluctuations

Investors often feel like they’re on a rollercoaster, where every new event seems significant. However, the reality is that most of us will invest for decades, possibly throughout our entire lives. Along the way, we will encounter numerous bull markets and corrections.

Given this, it’s surprising that we spend so little time preparing for these inevitable shifts and instead continue to react with shock to every market movement.

This guide aims to present a mental framework for better aligning with future market corrections. While it’s impossible to avoid the impact of market downturns entirely, we can certainly strive to manage the fluctuations of the investment journey more effectively.

1. Decoding Market Fluctuations

The stock market alternates between peace and turbulence. During a bull run, the market keeps making new highs before reaching a peak. Then, some adverse event happens, leading the market to fall and prices continue to decrease. After a while the decline stops and another up-trend begins.

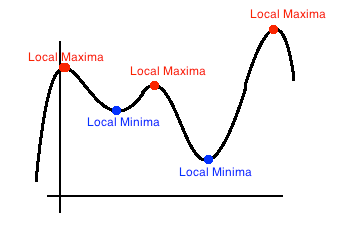

This pattern of alternating highs and lows brings to mind high school calculus and the concept of “Maxima and Minima”.

A Mental Model For Market Fluctuations

The Maxima is the maximum value “in a given interval” and the Minima is the minimum value in that interval.

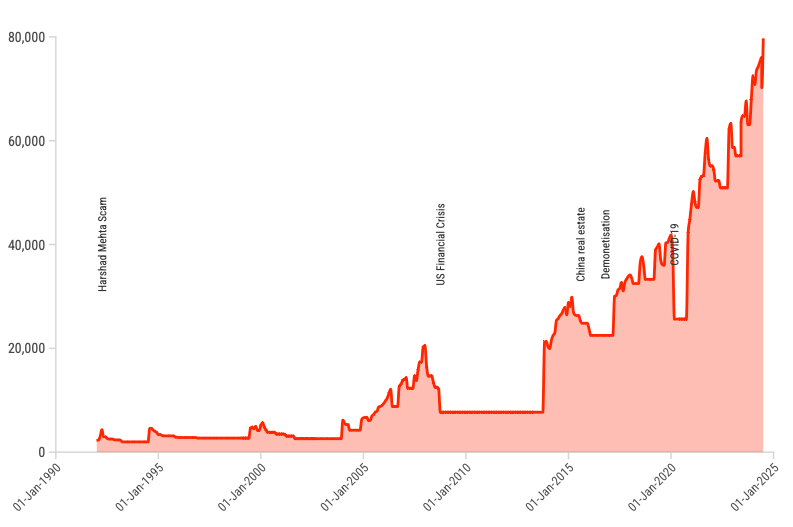

Look at the curve below – it has multiple peaks and troughs. Each peak is called a Maxima and each trough the Minima in that local interval or episode.

While a curve will have only one absolute global Maximum and Minimum value, it can have many maximas and minimas.

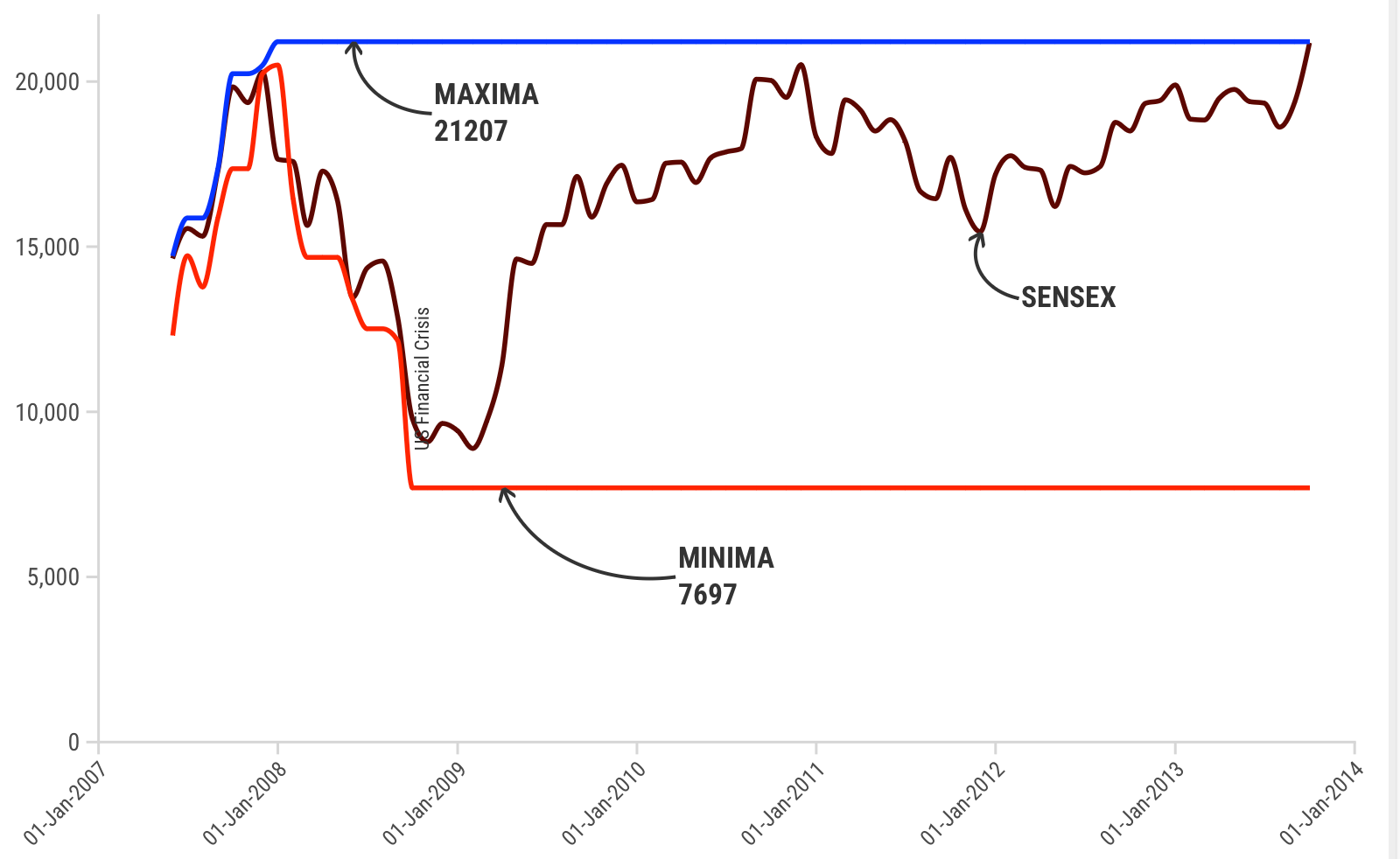

As stock prices fluctuate, the resulting price curve meanders and slopes, forming peaks and valleys. The figure below depicts the episode of the Great Financial Crisis in 2008.

Before the crisis, the Sensex had peaked in early 2008 at 21000. Then, after 14 months of fall, the market finally bottomed out at 7000 – a drop of 63%, the largest ever fall in the Indian markets.

Viewing stock prices as a series of episodes with their own high and low points is very useful. It becomes obvious that a significant increase in stock prices (like the current markets) will be followed by a decline sooner or later. And after every decline is over, the market will rise to form an even higher peak than before, as the cycle keeps repeating itself.

Let’s see how the Indian markets moved in terms of their Maxima and Minima over the last many years, starting with the Sensex Maxima.

This appears as a benign step curve that’s flat for long times and sloping upwards in the long-term. Any point on this curve represents the then maximum value of investor portfolios.

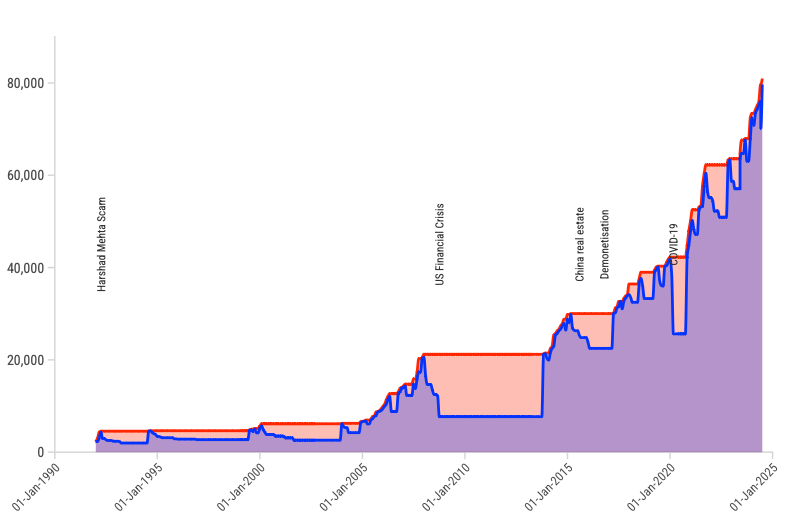

However, this curve conceals the volatility that the markets have endured. For that, let us plot the Minima.

This chart represents the market floor at any time. At all points on this curve, the investor portfolios were at their then maximum loss. One can see the real pain that investors had to endure.

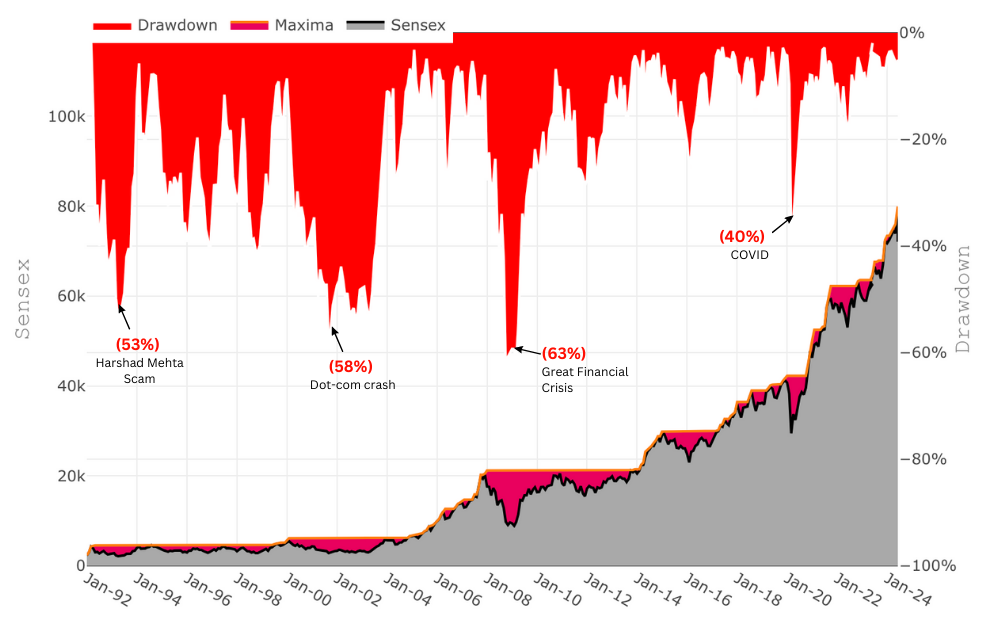

Combining the Minima and Maxima reveals the long-term market story. The red buckets depict the losses faced by investors from the previous peaks (also called drawdown losses simply drawdowns).

Note that the bucket representing the 2008 GFC fall is deep as well as wide – the pain lasted for a very long time as investor portfolios took years to get back to their 2008 highs.

The more recent COVID fall of 2020 appears as a deep but narrow bucket. The market crashed 40% in just a few weeks, but ended up recovering most of the losses in the same year.

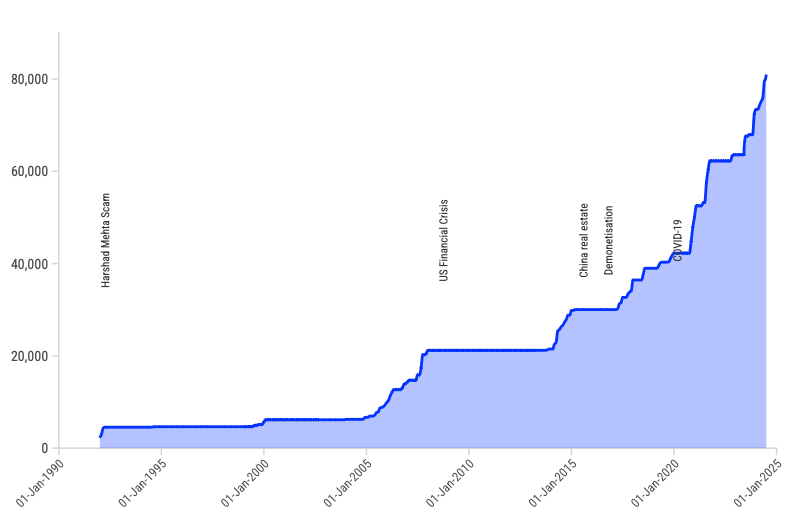

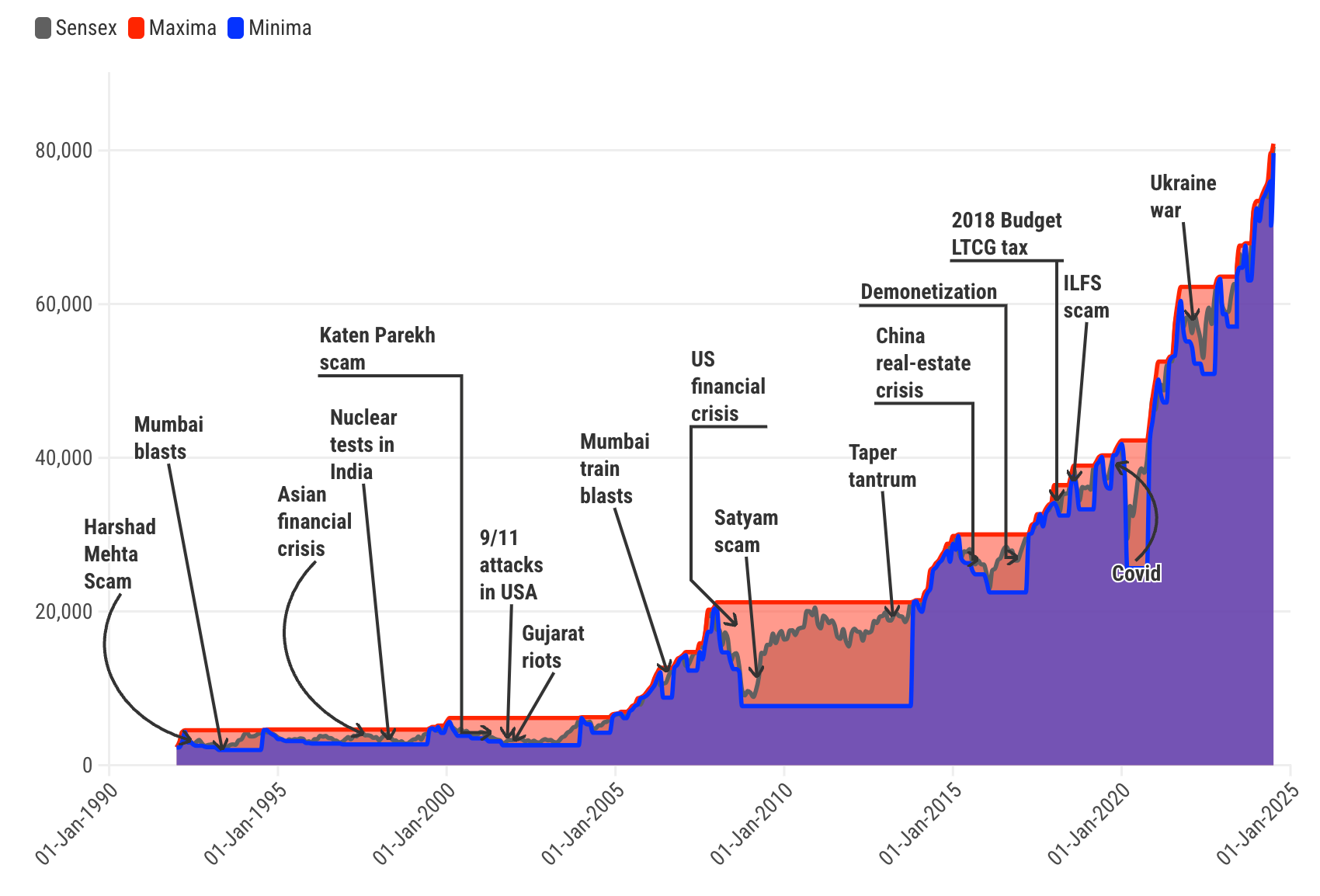

The figure below traces the Sensex over the past 30 years, overlaying the important crises that happened.

It becomes clear that the markets go up in the long term, but not in a straight line.

The long-term upwards movement is made up of many many episodes, each with its own local maxima and minima and accompanying drama.

The Psychological Impact On Investors

Ups and downs severely affect human psychology. The suspense of real-time price fluctuations weighs heavily on investors. There is no way that they can know in advance if markets are near the peak (in bull markets) or the bottom (in bear markets), since the Maxima and Minima can only be known in retrospect and not in real-time.

Let's consider the markets' fresh rise in a bear episode. Investors don’t know in real-time how far the market will rise, or if it's a false start and prices will crash again. Affected by the downturn, many investors end up selling their holdings at the first sign of appreciation.

As the market keeps rising, every small fall presents a dilemma: is it a normal pullback, or the first step of a prolonged downturn? If there were a bell to announce the peak, everyone could sell and avoid significant corrections. But since the future is unknown, investors are forced to deal with the uncertainty and discomfort as they hold on to their stocks.

Even experienced investors can be baffled by the continuous price increases in a bull market (like the current one).

Being an investor isn’t easy: if you sell and the markets go up, it leads to resentment. If you hold and they crash, you regret not selling at higher prices.

The markets will eventually fall in response to an adverse event. As the decline happens, it’s again unclear where the lowest point lies. For investors holding stocks, the losses accumulate. 20-30% wealth erosion is normal. But these losses seem greater due to loss aversion bias (a loss feels much worse than a similar gain).

As investors endure price drops for months, their survival instinct activates, tempting many to sell and cut their losses. This holds true for even the most experienced investors, since the market's potential decline remains uncertain.

Accepting The Inevitability Of Market Fluctuations

Viewing stock prices through the lens of Maxima & Minima has many advantages. Doing so, we explicitly acknowledge that the current drama is representative of the current interval. In the short and medium-term, the market will fluctuate, but the long-term trajectory will generally be upwards.

Also, it becomes clear that one cannot jump to a future Maxima bypassing the interim Minimas. This mental model promotes the long-term mindset and discipline required to remain invested and grow wealth over time.

2. Drawdowns & Corrections

As markets rise, the investor’s portfolio keeps growing, peaking near the Maxima. A very interesting thing happens here: at the peak, the highest value reached by the portfolio becomes the baseline in the investor’s mind.

Suppose the investor started with Rs 20 Lacs and their highest portfolio value stands at Rs 60 Lacs. The investor’s mind is now anchored to this number. So much so, that if the portfolio were to drop to 40 Lacs, it feels like a real loss. The reality is that the investor is making returns of 100% (20 Lacs –> 40 Lacs), but that is not how the mind operates.

Even a paper loss feels significant. This quirk of the human mind is called the anchoring bias.

As the market falls from its peak Maxima, investors incur losses called Drawdowns. The more the market falls, the more severe the drawdown. Drawdowns reach their maximum at the point of minima.

The chart below overlays the Sensex and its Maxima and Minima for the past 30 years. The drawdowns are shown coming from the top and measured as % loss.

During the 2008 financial crisis, the peak drawdown was 63%, meaning the average investor lost ~63% of their wealth compared to the previous peak. The losses of the Harshad Mehta scam of 1992 and the Dot-com crash of 2001 were in their 50s, while the recent Covid crash was 40%.

History shows that markets can fall, and fall significantly.

(Those who are further interested to rewind the markets and replay the drawdown losses can try this app)

Selling In Anticipation Of Market Decline

An obvious question arises here: why can’t smart investors sell at the peak of the bull market and avoid losses? This would save them much distress and, furthermore, they can buy back their holdings at the market’s bottom.

This is not easily done. As the bull market proceeds, the investor can’t predict the peak maxima. (The peak is only known in hindsight).

If an investor were to sell their holdings, and the market kept rising, it would invoke the worst kind of regret. It’s very tough to watch the stocks you sold keep rising. Most investors who end up in this position throw in the towel at some point and end up re-purchasing the same stocks at higher prices to alleviate their regret.

Ben Graham relates the story of Isaac Newton in The Intelligent Investor,

And back in the spring of 1720, Sir Isaac Newton owned shares in the South Sea Company, the hottest stock in England. Sensing that the market was getting out of hand, Newton dumped his South Sea shares, pocketing a 100% profit totaling £7,000.

But just months later, swept up in the wild enthusiasm of the market, Newton jumped back in at a much higher price—and lost £20,000 (or more than $3 million in today’s money).

Assume that one was more resolute than Newton and sold all their holdings at the market peak and even resisted buying at higher prices. Eventually, the market will fall and stock prices will drop below our investor’s sale price. The problem now is: when does the investor buy? Since the bottom of the correction is unknown, there’s no point at which one can purchase without facing immediate losses.

Also, buying large positions while the market news is bad and stocks are falling is extremely difficult, even for the experienced investors.

Our investor is caught like a deer in the headlights, with no idea what to do. In the process, he has permanently traded his long-term holdings. Bill Ackman nicely summed it up in a recent letter to his investors,

We do not typically sell our core portfolio holdings even if we believe it is highly probable that they will decline in price in the short term, as long as our view of their long-term potential remains largely unchanged.

A short-term trading program might enable us to avoid a small loss at the much larger cost of missing substantial stock price increases thereafter. As a result, we do not trade around our long-term holdings..

One may not always agree with Ackman's actions, but he is spot on here.

Living Through A Drawdown

When faced with drawdowns, the best course of action for an investor is to do nothing. The least that an investor must do is not sell their holdings during a correction, no matter how deep.

From a maxima and minima standpoint, a down period is simply the time before the next higher move that investors have to endure. (It is true that some stocks may never recover, but we’re discussing the market).

In this light, drawdowns are a feature of markets, not a bug. Long-term investors are not expected to nullify these losses, but rather expected to take them on their chin.

Imagine that markets had no volatility, crashes, and drawdowns. Then all investors would readily invest in equities, as they invest in Fixed Deposits, without the fear of any loss. Evidently, the returns on equities would mirror those of safer instruments.

Ergo, high returns cannot come free. Investors seeking them have to bear some risk. Drawdown losses are the price paid by long-term investors for earning larger returns. This is just how the process of risk works.

Charlie Munger had this to say to investors,

If you're not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century, you're not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you're going to get.

Market Bottoms are Great Opportunities

As the market keeps falling, every piece of bad news is accounted for. Most investors who needed to sell have already done so. At this point, it takes only a small amount of positive news for a new upward trend to begin.

Justin Mamis writes in The Nature of Risk,

The single best time to buy a stock – you can put this in your will for your grandchildren to rely on – is when, given bad news, the stock refuses to go down any more.

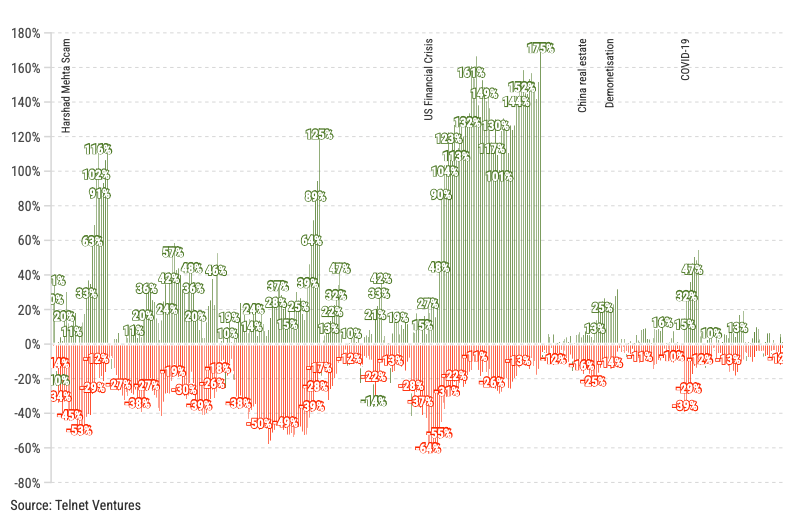

The below chart plots drawdown losses in red and the corresponding rise from the Minima in green, covering the past 30 years of the Sensex. As you can see, after every correction, the market consistently offers significant profits, although it takes some time.

Take the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, for example. The Sensex had a drawdown of over 60%. However, investors who bought at the bottom would have seen their investments appreciate by 100%-175% as the market recovered and reached new heights.

Bear markets offer long-term investors opportunities for significant gains at low risks. When fear peaks and the market absorbs negative sentiment, a powerful rebound is likely.

Stock market folks have a saying that "a stock that declines 50% must increase 100% to return to its original amount". Conversely, buying at the bottoms, when a stock is already down 50%, is the safest way to make 100% returns.

Another important point to note is that investors who are buying in a bear market don’t have to time the market’s absolute bottom. Purchases made at any level will make returns after the crisis is over and the market starts moving upwards. Obviously, buying at the bottom when the pain is highest will be more profitable than buying very early. (This is why when it gets gut-wrenching, it is a signal to buy).

However, buying during crises is easier said than done. With the investor’s psychology and survival instincts egging them to sell, it takes courage to step in and buy. One market guru commented that buying in crises "feels almost like death" while another said,

The very best stock purchases make you feel like throwing up.

Planning For Future Drawdowns

We have established that drawdowns are the price of admission to equity markets. Trying to avoid these losses can lead to sub-optimal returns.

But is there really nothing that the smart investor can do to prepare themselves for the impending correction?

Is it at least possible to soften the impact and ensure that we do not capitulate at the bottom of the market?

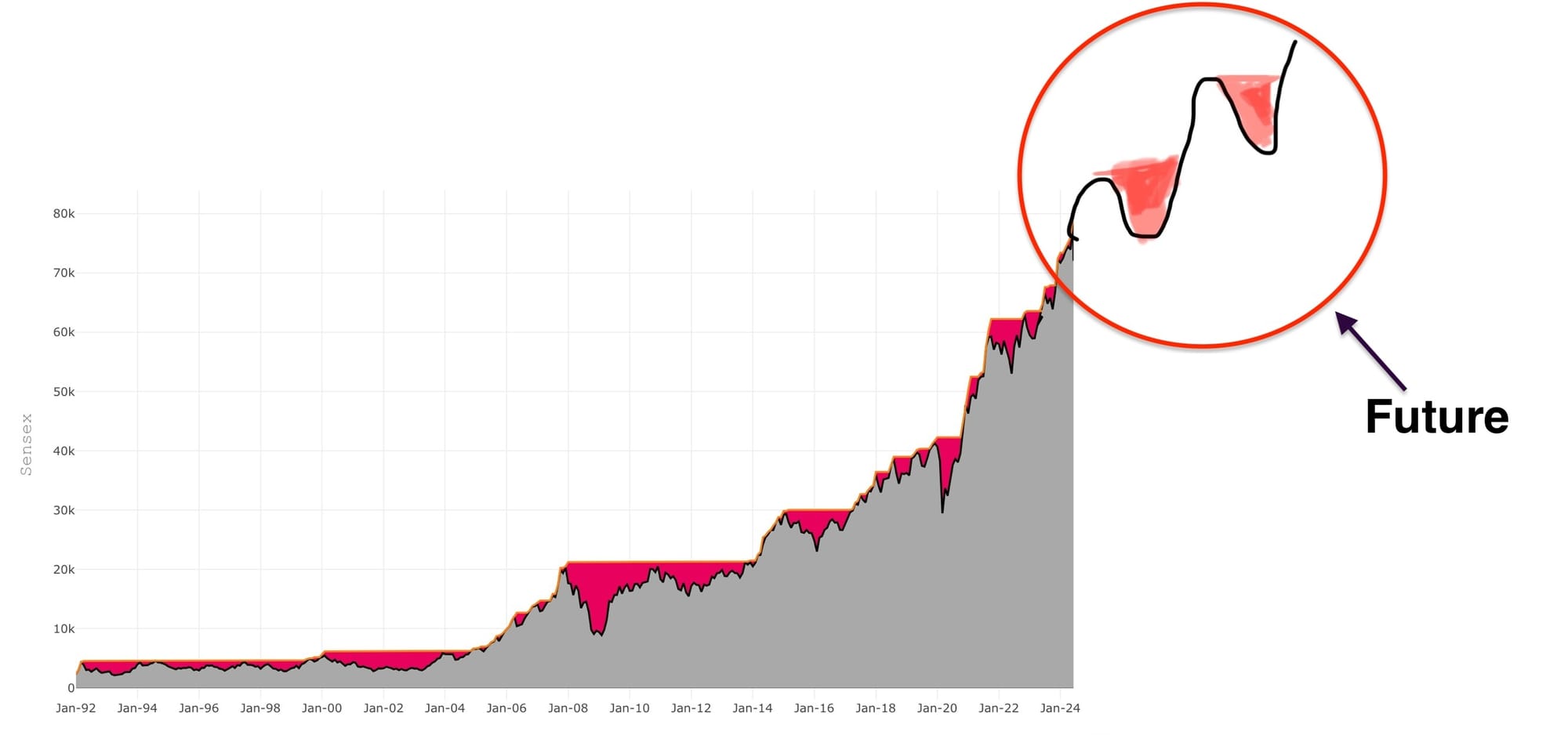

3. Positioning for the Next Market Phase

Through our explorations into Maxima, Minima, and Drawdowns, we have made some key observations:

- Markets can keep rising, and no one knows their limits. The peak of the market cannot be known in advance.

- Selling in bull markets feels foolish as stock prices continue to climb after the sale.

- Corrections cause markets to plummet to extreme lows. The bottom of the market is unknown in advance.

- Market declines are stressful and can easily lead to forced selling.

- The easiest profits come from buying in the bleakest market conditions. But, it is very challenging to buy at market lows.

- The markets will move from Maxima to Minima, and an even higher Maxima.

Let’s use these insights to create an action matrix for long-term individual investors.

In Bear Markets |

|

| Key action | BUY |

| ↳ When | Strong corrections generally lead to 20-25% drawdowns. It’s wise to wait before buying, as investors have limited cash. A good rule is to buy only when it is gut-wrenching. |

| ↳ What | Buying in a crisis is difficult. One should aim to buy more of what they understand thoroughly. |

| ↳ How much | Consider purchasing in 2-3 installments. Timing the bottom isn’t essential. |

| ↳ Aftermath | The market will continue to decline after buying, leading to losses. |

| ↳ Mindset | The immediate losses upon buying will lead to regret and introspection. However, this discomfort is an essential part of the investment process during bear markets. |

In Bull Markets |

|

| Key action | SELL |

| ↳ When | Avoid selling until optimism is high and memories of the previous bear market have faded. |

| ↳ What | Sell a small % of the portfolio. Selling some stocks entirely can create unhealthy psychology if they increase further. |

| ↳ How much | Sell a small portion (e.g., 5%) of the portfolio every 6-12 months. |

| ↳ Aftermath | After selling, the market will continue to rise. |

| ↳ Mindset | The market rise after selling will lead to regret, which is the desired psychological state. |

In this framework, the investor is expected to act only in the late stages of both bull and bear markets. The recommended actions counter prevailing market behaviors and are designed to induce regret, positioning the investor as a (minor) contrarian, which is the goal.

Selling during bull markets can be emotionally taxing, but it’s a valuable strategy. As the market continues to rise post-selling, the investor will experience regret, leading to resentment towards further gains. This mental state prepares them for the next cycle. Some may even privately wish for a pullback to invest their cash at more favorable valuations!

Looking foolish at market extremes is necessary for making money in the longer term.

It's important to note that the amount of selling isn't as critical as the act itself. Even selling a small portion can generate the necessary regret and emotional conditioning to navigate the next market downturn. For instance, selling just 5% and retaining 90% may still cause significant regret as the market continues to rise.

I recently spoke to a prominent HNI investor who was regretting selling a multi-bagger stock (that he had held for years), because it had sharply appreciated after his sale. Later, I gathered that he had sold only 20% of his holdings and continues to hold the rest!

An investor who has already sold is both mentally and financially prepared to buy.

This forced-contrarian mindset allows long-term investors to anticipate sentiment shifts in advance. This also explains why successful investors hold more cash during bull markets, preparing for the next downturn.

By embracing the emotional challenge of selling during bull markets, investors develop the mental strength to stay through the down cycle without capitulating, and also have some cash available to take advantage of juicy valuations.

Conclusion

Making Peace With The Market

In this series, we compared stock market gyrations as a series of maxima and minima. This mental model makes it obvious that one cannot jump to a future maxima without enduring the minimas in between.

Consequently, drawdown losses that occur during market corrections are a necessary cost of achieving substantial long-term returns. Even the most well-prepared investors are not expected to avoid them.

One active strategy that long-term investors can consider is to align their psychology against the crowd at market extremes – by selling a (small) portion of their holdings at bull-market highs and buying during corrections. While these actions are bound to cause immediate regret, they are useful in preparing investors for the next phase of the market cycle.

For long-term individual investors, this approach is preferable to a pure buy-and-hold strategy because it aligns their psychology with the market's next stage, reducing the risk of panic selling at market bottoms.